During the holiday season, groups like Heifer International and Oxfam ramp up their “animal gifting” donation campaigns with a deluge of catalogs and emails encouraging people to “gift” farmed animals to food insecure families in developing countries.

These campaigns are popular despite animal agriculture being a leading contributor to climate change and food insecurity.

Headline after headline reaffirms that the world’s most food insecure populations are those most harmed by climate-intensified events— including increased drought, hurricanes, tsunamis, flooding, and other extreme weather events.

Of the current flooding crisis in Chennai, India’s leading meteorologist— along with its prime minister— both link the disaster to human-caused climate change.

And in Syria, journalists pinpoint climate crises as a major factor in the current conflict of a region devastated by unprecedented drought and desertification, with the latter greatly exacerbated by overgrazing. Writing in The Ecologist, journalist Gianluca Serra observes:

“A major role in this unfolding disaster was played by affluent urban investors who threw thousands of livestock into the steppe, turning the grazing into a large-scale, totally unsustainable, industrial practice.”

While animal-gifting programs such as Heifer International seem to focus on small-scale farming, in actuality they have extremely large-scale implications that pave the way for factory farming and drastically increase consumption of meat, dairy and eggs throughout entire countries and beyond.

To cite one example, Heifer International is largely considered responsible for the kick-off of industrialized dairy in Japan after World War II. Additionally, Heifer boasts that their projects produced 3.6 million gallons of milk in one year in Uganda, and developed a national dairy program in Tanzania.

These massive programs were developed despite the high prevalence of lactose intolerance in these regions (more than 90% of the population in some Asian and African countries) and despite the fact that native plant crops are capable of producing equal or greater amounts of protein, calcium and other nutrients.

The World Food Programme writes, “Climate change is a hunger risk multiplier, threatening to undermine hard-won gains in eradicating hunger and poverty. Current projections indicate that unless considerable efforts are made to improve vulnerable people’s resilience, 20 percent more people will be at risk of hunger by 2050 due to the changing climate.”

But it’s not just via climate change that animal agriculture contributes to food insecurity. Farming animals is notoriously inefficient and wasteful when compared to growing plants to feed humans directly, with the end result that “livestock” animals take drastically more food from the global food supply than they provide.

This is because in order to eat farmed animals, we have to grow the crops necessary to feed them, which amounts to vastly more crops than it would take to feed humans directly. (In 2023, we feed and slaughter some 75+ billion land animals every year; there are 8+ billion humans on earth).

To give one example, it takes 25 pounds of grain to yield just one pound of beef — while crops such as soy and lentils produce, pound for pound, as much protein as beef, and sometimes more.

Compounding this inefficiency is the fact that only a small fraction of the plant energy consumed by an animal is converted into edible protein. Most of the energy from crops fed to farmed animals is used to fuel their own metabolism, with only a fraction of those grains and other plants being turned into meat.

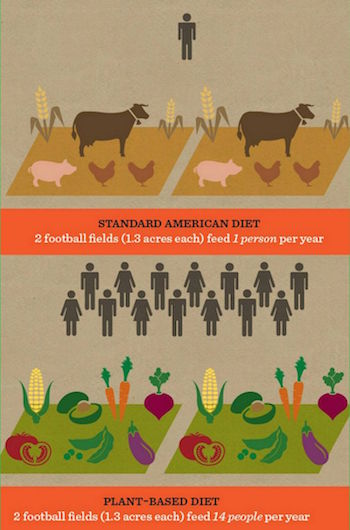

Then there’s the land. One acre of land can yield between 2-20 times more plant food than animal-based foods. Writes Richard Oppenlander, “We are essentially using twenty times the amount of land and crops, and hundreds of times the water, as well as polluting our waterways and air and destroying rainforests, to produce animals to kill and eat … which is unhealthier than eating the plant products we could have produced.”

In fact, analysis of global agricultural yields finds that better use of existing croplands could feed four billion more people simply by shifting away from growing crops for animal feed and fuel, and instead growing crops for direct human consumption. Reallocating croplands in this way could increase available global food calories by as much as 70 percent, according to researchers.

Now more than ever, efforts to reduce global hunger should focus on sustainable plant-based approaches wherever possible.

For these reasons and more, our hunger grants specifically support outstanding groups and individuals doing effective work with plant-based feeding and/or farming projects. Our Plants-4-Hunger gift-giving campaign features four exceptional groups alleviating hunger without using animals. We send 100% of donations to these groups working to provide both immediate assistance and long-term community solutions to improve food security and nutrition.

If you’d like to donate or make a gift in someone else’s name, please visit our Plants-4-Hunger page. To learn more about the harms of animal gifting programs, please see our feature, Reasons to Say NO to Farmed Animal Gifting.