With the human population expected to exceed nine billion people by 2050, and meat consumption drastically increasing, it is estimated that we will need two-thirds more land than the earth actually has in order to meet predicted demand for food (especially of animal origin) over the next 25 years.

These troubling figures arrive in large part because farming animals is immensely inefficient and wasteful when compared to growing plants to feed humans directly. In short, farmed animals consume massive amounts more food than they produce.

Even the United Nations acknowledges that animal agriculture is responsible for more greenhouse gases than all transportation combined, and that a global shift away from meat and dairy is needed to mitigate the worst impacts of climate change and world hunger.

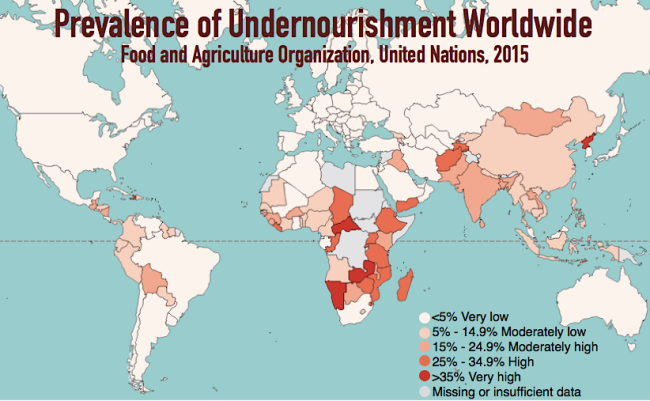

This is especially important as the world’s most food insecure populations are often those most harmed by climate change-related events, including increased drought, hurricanes, tsunamis, and flooding.

The World Food Programme writes, “Climate change is a hunger risk multiplier, threatening to undermine hard-won gains in eradicating hunger and poverty. Current projections indicate that unless considerable efforts are made to improve vulnerable people’s resilience, 20 percent more people will be at risk of hunger by 2050 due to the changing climate.”

For these reasons and more, our global hunger grants specifically support outstanding groups and individuals doing effective work with plant-based feeding and/or farming projects.

Below, we highlight seven powerful ways that plant-based foods and farming approaches are alleviating hunger without using animals; improving food security and nutrition; providing income and self-sustaining livelihoods; and building/empowering communities.

1. Community Food Gardens

2. Food-Bearing Trees

3. Gleaners

4. Floating Gardens

5. Mobile Farmer’s Markets

6. Climate-Resilient Indigenous Crops

7. Global Seed Sharing

Community Food Gardens

Grow Where You Are is a team of veganic farmers and food justice activists in Atlanta doing revolutionary work in the areas of food security, ecological restoration, vegan outreach, and animal-free growing techniques. Since 2009, Grow Where You Are has been empowering individuals and families to improve their personal food security by planting backyard and community food gardens. These gardens can drastically increase families’ access to fresh fruits and vegetables in urban food deserts.

GWYA also partners with land-owning churches to install and manage organic vegetable micro farms in struggling urban neighborhoods on community land that would otherwise sit unused. Produce from these urban farms is used to feed volunteers and to stock produce stalls that GWYA sets up in Atlanta’s food deserts— areas that otherwise have little to no access to nutritious fresh fruits and veggies.

For other great community garden initiatives that we support, check out Health in the Hood, the Food is Free Project, and Kitchen Gardeners International. See also our Ethiopian School Lunch Program in partnership with International Fund for Africa.

Food-Bearing Trees

More than 80% of the world's hungry live in tropical and subtropical regions. Many of these people depend on subsistence agriculture for both food and livelihood, yet live in areas where poor soil fertility and unreliable rainfall result in poor crop yields, leading to food insecurity and malnutrition. However, many of these countries have environments well-suited to cultivating climate-resilient, food-bearing trees.

Fruit and nut trees maximize food output while minimizing land and resource inputs, restore ecological balance to land damaged by misuse, capture and sequester carbon dioxide to offset global warming, and create habitat for small animals and birds. They are also more climate resilient than many vegetable crops.

A Well-Fed World specifically supports Sadhana Forest, a non-profit that plants sustainable food forests and implements water reclamation projects in arid communities in India, Haiti and Kenya. Their operative concept is simple: plant indigenous food trees in arid regions that were once forested but have since become degraded, useless land.

In Kenya, for example, Samburu County is one of the regions most devastated by recurrent drought, and most of the population lives in poverty. Climate change has made cattle herding an increasingly untenable livelihood for nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralists, exacerbating hunger and food insecurity.

Sadhana Forest is working to help the Samburu community reforest their region with 18 species of indigenous drought-resistant fruit trees. These food-bearing trees are rich in nutrients and, in addition to increasing food security, will also improve soil quality and water absorption rates, making desertified earth better suited to growing food crops.

We also support the Fruit Tree Planting Foundation, an international charity dedicated to planting fruit trees to alleviate world hunger, combat global warming, strengthen communities, and improve the surrounding air, soil, and water. FTPF plants and donates orchards, training, and aftercare where harvests will best serve communities for generations -- including public schools, city parks, community gardens, food banks, low-income neighborhoods, Native American reservations, international hunger relief sites, and animal sanctuaries.

Specifically, A Well-Fed World is pleased to sponsor Fruit Tree Planting Foundation's reforestation and job creation project in the Peruvian Amazon. This tree planting project provides families in five communities, whose average monthly earnings are less than $35, with a source of perennial income. In a region that is only accessible by boat, these native food trees provide families with nourishment and a sustainable source of income without cutting any trees down.

We have also supported the Trees That Feed Foundation, which provides food to communities in need through the planting of food-bearing trees with edible fruit and high yields. To date, Trees That Feed has planted more than 60,000 food-bearing trees around the world, which not only feed people in need, but provide a healthy alternative to consuming animal products.

Read more: At Sadhana Forest, Trees Spring From Once-Barren Land

Kenyan Pastoralists Fighting Climate Change Through Food Forests

Potential of Indigenous Fruit-Bearing Trees to Curb Malnutrition, Improve Household Food Security, Income and Community Health

Gleaners (Food Rescue)

Gleaning has historically referred to the long-standing tradition of community members picking surplus fruits and vegetables from fields after farmers have done their harvesting. In some cultures, gleaning has long existed as a form of of food aid to those in need. Modern day gleaning (sometimes referred to as “food rescue”) also includes initiatives to partner with local restaurants, grocers, bakeries, farmer's markets, etc to pick up or "rescue" food that would otherwise be thrown out.

One such group is Food Forward in Los Angeles. Food Forward was founded by photojournalist Rick Nahmias, whose experiences documenting migrant workers left him moved by “the sad irony of people harvesting our food who can’t afford to buy it themselves.”

Rick first founded Food Forward as a fruit tree gleaning initiative, but the organization’s programs now include a Farmer’s Market Recovery program for produce that doesn’t sell, and an extensive Wholesale Produce Recovery program that rescues millions of pounds of viable produce every year from large distributors, donating 100% to local agencies who feed the community’s most vulnerable people.

The organization also operates an active Backyard Harvesting program, where volunteers and neighbors obtain permission to pick fruit from residential yards where it would otherwise go to waste, and distribute it to people who are food insecure in their communities. Food Forward was featured along with several other great groups in this recent article on modern-day gleaners.

Interested in starting a gleaning group in your community? Check out this comprehensive how-to guide.

Floating Gardens

Bangladesh has the highest wetland to total land ratio in the world: nearly half of the country’s entire area is comprised of wetlands. Increasing climate disruptions (Bangladesh is disproportionately affected by monsoons and flooding) are leading to greater pressure on these already fragile agricultural lands, and are leaving a growing segment of the population landless.

In response to the need for increased crop yields, synthetic fertilizers and pesticides have been introduced in many areas, bringing with them a host of negative environmental impacts. As an alternative to these methods, some NGOs have begun focusing their efforts on the cultivation of floating farms, or “soil-less agriculture,” which has been practiced in parts of Bangladesh for hundreds of years.

How does it work? For a base, floating gardens commonly employ a type of water hyacinth that is prolific in waterways all over South Asia. Water hyacinth and bamboo are woven into a buoyant platform onto which layers of mulch, soil and compost are built up. Seeds can then be sown on the platforms, which can produce up to ten times more harvest than planting on dry land.

Crops that do well on floating gardens include leafy vegetables, lettuces, beans, cabbage, chili peppers, okra, cucumber, eggplant, garlic, spinach, pumpkin, onion, potato, tomato, water arum, and other vegetables. The floating gardens can be used for both summer and winter crops.

In addition to providing food for the grower's family, floating gardens also provide income through sale in the local market. There is little food in the markets during monsoon, as few people can grow crops, so vegetables sold from floating gardens are in great demand.

“The productivity of this farming system is 10 times higher than traditional land-based agricultural production in the southeast of Bangladesh,” said Papon Deb, project manager for the Wetland Resource Development Society (WRDS), one of several NGOs working around the country to train thousands of farmers in this traditional farming technique.

Learn more about floating gardens:

BANGLADESH: Spreading the floating farms’ tradition

Cultivating Wetlands in Bangladesh

Floating Gardens in Bangladesh

Mobile Farmer’s Markets

More than 23 million people in the United States live in food deserts – urban neighborhoods and rural towns without ready access to fresh, nutritious, and affordable foods. Instead of supermarkets and grocery stores, these communities often have nothing but fast food restaurants and convenience stores that offer little in the way of healthy food or fresh produce. Lack of access to fruits and vegetables contributes to malnutrition and leads to higher levels of obesity and other diet-related diseases, including diabetes and heart disease.

In Central Florida, where more than 90,000 residents live in food deserts, The Fresh Stop Bus functions as a mobile farmer's market that travels to underserved neighborhoods, providing fresh fruits and vegetables at affordable prices. The bus is a re-purposed public transportation vehicle outfitted with special refrigerated racks for fresh produce.

In addition to its current 16 food desert stops, The Fresh Stop Bus also visits Cheney Elementary School, where a high percentage of students come from low-income households with limited access to fresh produce outside of school. One day a week, after the last school bell rings to signal the end of classes, Fresh Stop sets up in the school parking lot, with the goal of increasing access to, and consumption of, fresh fruits and vegetables among students, their parents/guardians, and school staff.

Learn more about The Fresh Stop Bus at their website and Facebook page. You can also support their fundraiser.

Climate-Resilient Indigenous Crops

Across sub-Saharan Africa, more than 2,000 native grains, legumes, roots, vegetables, cereals, fruits and other food crops have been used to nourish people for thousands of years. But since the 1960s, with Western models for increasing crop yields dominating the global landscape, agriculture has primarily focused on cultivation of staple food crops such as rice, wheat and maize, often to the neglect of valuable native wild edibles.

Increasingly, though, agricultural researchers and nutritional experts are promoting the value of indigenous fruits and vegetables in areas most affected by climate change and hunger. Indigenous food plants are often richer in nutrients than domesticated non-native crops, and they are better able to endure droughts and pests. This makes native edibles an important tool to reduce climate vulnerability and dietary deficiencies.

"I don't believe we can address the issues of nutrition security, poverty, and health in Kenya without relying on African indigenous crops,” says Mary Abukutsa-Onyango, a horticultural researcher in Kenya who has devoted her career to studying and popularizing the potential of African indigenous vegetables. “With a soaring food crisis, and maize harvests predicted to be 16 percent below former years as a result of changing Kenyan weather patterns, the only grains that could adequately replace maize in my opinion would be indigenous millets and sorghum, which are more drought tolerant.”

Luigi Guarino, a senior scientist with the plant research organization Global Crop Diversity Trust, echoes the sentiment, emphasizing that warmer temperatures are changing what people are able to grow in some regions. "A lot of people in south and east Africa will have to move away from maize, which is the main staple at the moment." In order to mitigate lower yields for a key food source in a region where one in four still do not get enough to eat, farmers should “switch to sorghum, millet and traditional vegetables like African nightshade or spider plant.

In some areas, indigenous crops also present a more viable and sustainable option for farmers than raising animals for food. In Ethiopia, for example, “over 40 percent of the population is considered hungry or starving, yet the country has 50 million cattle (one of the largest herds in the world), as well as almost 50 million sheep and goats, and 35 million chickens, unnecessarily consuming the food, land and water,” writes Richard Oppenlander in Food Choice and Sustainability. “[P]oorly managed cattle grazing has caused severe overgrazing, deforestation, and then subsequent erosion and eventual desertification. Much of their resource use must be focused on these cattle.

Instead of using their food, water, topsoil, and massive amounts of land and energy to raise animals for food, Ethiopia, for instance, could grow more teff, an ancient and quite nutritious grain grown in that country for the past 20,000 to 30,000 years. Teff…is high in protein, with an excellent amino acid profile, is high in fiber and calcium, (one cup of teff provides more calcium than a cup of milk), and is a rich source of boron, copper, phosphorus, zinc, and iron.

Seventy percent of all Ethiopia’s cattle are raised pastorally in the highlands of their country, where less than 100 pounds of meat and a few gallons of milk are produced per acre of land used. Researchers have found that teff can be grown in those same areas by the same farmers at a yield of 2,000 to 3,000 pounds per acre, with more sustainable growing techniques employed and no water irrigation— teff has been shown to grow well in water-stressed areas and it is pest resistant.”

Read more about the ways indigenous plants reduce hunger:

Neglected Indigenous Food Crops Could Be a Saviour

A Wild Solution to Hunger: Farming Native Plants

The Role of Wild Vegetables in Household Food Security in South Africa

Solving Hunger in Ethiopia by Turning to Native Crops

Kenya: Farmers in Tharaka Nithi County Fight Hunger Through Indigenous Crops

The Rise of Africa's Super Vegetables

Global Seed Sharing

Seed Programs International provides quality seeds, along with training in optimal growing techniques, to impoverished communities in developing countries where good seed access is limited or scarce, enabling them to grow their own food. To date, SPI has shipped enough seed to plant over 1,000,000 vegetable gardens, providing more than 20 kinds of vegetables that are rich in vitamins and minerals often missing in undernourished people’s diets.

Through partnerships with leading seed growers worldwide, SPI secures donations of surplus non-GMO seeds that would otherwise be discarded. SPI tests the seeds for quality, vitality and germination rates, then packages viable seeds in individual garden packets with instructions for growing printed in multiple languages on the back of each package.

SPI also focuses on improving food security during disasters.

SPI also focuses on improving food security during disasters.

A Well-Fed World recently sponsored a shipment of SPI seeds to Liberia, where the spread of Ebola spurred price hikes and food shortages.

In a country where so many already live on less than $2 a day, finding nutritious food becomes nearly impossible as travel is restricted and markets cease to function. Growing one’s own food is often the best solution during such crises, but while many people can access land in Liberia, few have good seeds.

A recent recipient of seed there writes, “When they told me about these seeds, I did not show any interest because I thought it was just some of those seeds that always fail to grow. I reluctantly took a few packets and tried them. The peppers germinated so fine that I got encouraged and went back to acquire more. They grew so fine and transplanted and the yield was good. I am very happy and proud of these seeds. It helped me this year to take care of the many problems that I was faced with. Now we are looking healthy and strong. Thanks to all the people who are making it possible for us to continue to survive. Let’s continue to work together; even though we don’t know you in person, we can feel the love you have for us."

Learn More

To learn more about the plant-based feeding and farming projects we sponsor and why, check out our hunger grants, global hunger, and no animal "gifts" pages.

Thank you to our compassionate donors for supporting these life-changing projects. If you would like to expand our reach, please visit our Plants-4-Hunger program, or click here to donate now.