Hunger relief charities that promote sending live cows, goats, and chickens as “gifts” to families experiencing food insecurity and hunger often present animal farming as the default “best” way to feed people and help bring them out of poverty.

“Send a cow’ and “give a goat” campaigns focus on increasing “livestock” production not because animal agriculture is inherently better for the recipients or the regions they live in; and not because this is the only, or even the best, way to reduce hunger and poverty in these communities.

Rather, the emphasis on “gifting” farmed animals reflects Western culture’s entrenched pro-meat-and-dairy biases, and the default dominionist paradigm (animals simply exist for us to own and use) that underpins so many food aid charities.

But promoting increased animal farming is increasingly at odds with recommendations from climate scientists and food security experts, who emphasize the urgent need for drastic reductions in meat and dairy production and consumption, pointing to animal agriculture’s disproportionate greenhouse gas emissions, as well its inherent inefficiency and massive overuse of resources when compared to plant food production.

Plant Foods Feed Far More People Using Far Fewer Resources

Meat and dairy provide just 18% of global calories but use 83% of global farmland. In a recent study being hailed as the most large scale and comprehensive analysis to date of farming’s environmental impacts, published in the journal Science and led by scientists at the University of Oxford, researchers concluded that without meat and dairy consumption, global farmland use could be reduced by more than 75% and still feed the world.

In fact, the United Nations Environment Program, in a report on global food security, estimates that we could feed 3.5 billion more people simply by shifting away from growing crops for animal feed and instead growing crops for human consumption.

It takes far more land, water, crops, and energy to raise, house and slaughter 75+ billion land animals every year than it takes to grow crops to feed humans directly. We are running out of land, decimating earth’s forests, and driving wildlife extinct at unprecedented rates as a result of habitat loss caused by meat and dairy farming.

Climate Change is Causing Livestock Herders to Grow Crops Instead

Defenders of animal gifting programs, many of which encourage supporters to purchase cows and goats for families in countries experiencing extreme hunger and poverty, often point to traditions such as African pastoralism and nomadic herders’ longstanding reliance on livestock for sustenance. However, pastoralists are increasingly shifting to growing drought tolerant crops and climate resilient, indigenous fruits and vegetables instead, in response to climate change.

“Samburu County is one of the regions in Kenya most ravaged by recurrent drought, with most of the population living below the poverty line. Climate change has made cattle herding an increasingly unsustainable livelihood option for nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralists, leaving many households in Samburu without access to a daily meal.

Samburu community leader Joshua Leparashau says, “Animals will continue to die due to severe drought. The community still wants to hold on to the concept that having many livestock is a source of pride. This must change.” He and other community leaders note the need for decreased dependence on animals and increased cultivation of plants and food-bearing trees.

In response, the Samburu tribe, working with Sadhana Forest, has embarked on an initiative to plant 18 species of indigenous drought-resistant fruit trees and shrubs. These food-bearing trees are rich in nutrients and, in addition to increasing food security, improve soil quality and water absorption rates, making desertified earth better suited to growing plant food crops.

Elsewhere in Kenya, extreme heat and increased droughts have taken a similar toll. As a result, more than 100 livestock farmers in the region have begun growing chili peppers instead. Reporting for Reuters earlier this year, Caroline Wambui writes:

“In this arid stretch of Kajiado County, where worsening heat and drought have been tough on livestock farmers, Arnold Ole Kapurua is experimenting with a hot new crop: chilis.

Ole Kapurua, 29, a farmer and agronomist, now grows two acres of the fiery pods – and is training other farmers to do the same – as a way to protect their incomes in the face of harsher weather linked to climate change.

‘With time we realised that we weren’t making good money as our livestock income stagnated… During drought we lost our herds to hunger and diseases, while during the rainy season we lost some to floods, making us live on a lean budget.’

While some farmers still rely entirely on livestock in the region, a growing number are now concentrating their energy on farming chili, which can be grown with limited amounts of water, said Samuel Ole Kangangi’r, another new chili farmer.

Over the last five years, more than 100 farmers in the region have begun growing chilis… Well-managed chili farms can produce an ongoing harvest over six months, with an acre of land producing up to two tonnes of peppers a week, Ole Kapurua said.

‘That level of harvest can bring as much as 80,000 Kenyan shillings ($800) a season,’ he said.

‘That cannot be compared to livestock rearing as one cannot afford to be selling a cow every week, thus making chili farming a better option.’”

“Recurring and frequent drought in arid and semi-arid regions of northeast Kenya has forced pastoralists to abandon livestock rearing and engage in irrigation farming.

The Dololomide farm group in Sankuri, Garissa County that consist of 60 members are now engaging in sorghum and cow peas irrigation farming after they lost most of their livestock to drought.

‘We decided to try our hands at irrigation farming instead of waiting for handouts from the government. With the support of relevant agencies, we are slowly and surely succeeding,” group chairman Hassan Mohamed said on Thursday.”

“[T]he county is classified as food insecure because it receives 280 mm of rain in two seasons combined, which he said cannot support the generation of the preferred maize.

‘As one of the lead agencies involved in food security, we put our heads together and agreed that the only way we can engage the farmers was to urge them to venture into farming of sorghum, which is drought tolerant,’ he added.

He regretted that Garissa County depends on famine relief food throughout the year and noted that the project is a demonstration to the farming community and other stakeholders of the need to move away from relief dependency syndrome to a food secure situation by adopting drought resistance crops like sorghum.”

“Before we thought of growing crops, we depended on livestock for our livelihood. We also ate wild fruits to supplement the meat and milk from our livestock. But this has been a dry area for very long and rain is scarce. Frequent drought left our animals emaciated and many times they die,” says Selina Ekipor, a mother of four boys and 2 girls.

“We are proud that we are learning how to grow our own food. We grow sorghum, cowpeas, green grams and maize. Life is better now that we are farming.”

Nangor Lobongia is another former herder turned smallholder farmer who is now growing sorghum and maize.

“I sing for joy as I harvest my crop,” says Nangor, a widowed mother of seven. “The last three years were very difficult, and for the first time, my family does not depend on aid.”

With the help of World Food Program, Selina, Nangor and other women in their community are learning rainwater harvesting techniques such as digging water pans, construction of bunds—structures that help retain the water—as well as simple irrigation methods.

Adds former pastoralist Sara Ekwuam, “Previously my family depended on pastoralism but over time the rains became less and less, and we were unable to find pasture and water for our livestock. As a result, we were forced to depend on relief food and supplies.”

But, she adds, with the help of rainwater harvesting and micro-irrigation, “Although we did not get a lot of rain, the water in the bunds was enough to grow this sorghum crop to maturity. I harvested 10 bags. I will sell five of them to buy other things that I need.”

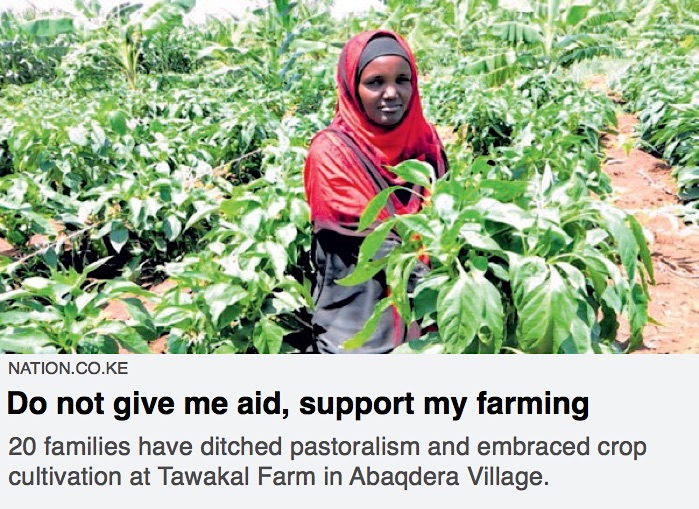

Isnina Bille, mother of eight, is among 20 families who gave up pastoralism and began crop cultivation at Tawakal Farm in Abaqdera Village, where her family moved from Somalia in 2011 in order to obtain food aid.

That year, the Horn of Africa suffered one of its worst hunger epidemics, devastating more than 13 million people in Ethiopia, Northern Kenya, Djibouti and Somalia. “We lost all our goats. My family had 350 sheep, and only 35 survived,” says Bille.

Isnina made a bold move against tradition in her decision to try crop farming, and was met with great resistance from her husband and community members.

“My husband did not want to get involved because [crop] farming is considered a taboo among the Somali community. The number of livestock one has defines their (financial) status,” she explained.

Despite the initial pushback, Isnina is now in her third growing season and successfully produces watermelon, maize, capsicum, and bananas.

“After the first harvest, I managed to make Sh64,000. With the proceeds, I opened a shop in town, which my husband operates,” she says.

Bille is now considered a leader in helping to eradicate cultural stigma around, and resistance to, crop farming among the Somali people.

“As women, we are perceived as only capable of milking goats and taking care of the children. But today, we are not only the main farmers, but the farm managers.”

A Return to Indigenous Plant Crops Essential to African Food Security

One effect of Western food aid programs that focus on increasing meat and dairy production and consumption is the erasure of more nutritionally appropriate and culturally relevant indigenous foods. Across sub-Saharan Africa, more than 2,000 native grains, legumes, roots, vegetables, cereals, fruits and other food crops have been used to nourish people for thousands of years. But since the 1960s, with Western models for increasing food yields dominating the global landscape, agriculture has primarily focused on intensification of livestock production, and cultivation of staple food crops such as rice, wheat and maize, often to the neglect of valuable native wild edibles.

Increasingly, though, agricultural researchers and nutritional experts are promoting the value of indigenous fruits and vegetables in areas most affected by climate change and hunger. Indigenous food plants are often richer in nutrients than domesticated non-native crops, and they are better able to endure droughts and pests. This makes native edibles an important tool to reduce climate vulnerability and dietary deficiencies.

“With a soaring food crisis, and maize harvests predicted to be 16 percent below former years as a result of changing Kenyan weather patterns… I don’t believe we can address the issues of nutrition, security, poverty, and health in Kenya without relying on African indigenous crops,” says Mary Abukutsa-Onyango, a horticultural researcher in Kenya who has devoted her career to studying and popularizing the potential of African indigenous vegetables.

Abukutsa-Onyango’s focus is on native edible plants whose nutritional and healing benefits have been nearly erased from popular knowledge through decades of Western influence on African agricultural practices. Her outreach emphasizes that plants such as amaranth greens, spider plant, and African nightshade, commonly relegated to the status of “weeds,” in fact contain substantial protein and iron and are rich in calcium, folate, and vitamins A, C, and E.

Climate change, deforestation, habitat loss, and resource scarcity, of which animal agriculture is a leading cause, mean we need reductions, and not expansion, of animal farming. For this and many other reasons, efforts to combat hunger and food insecurity should focus on sustainable plant-based approaches wherever possible.

Plants-4-Hunger: Nourishing People and the Planet

Our Plants-4-Hunger gifting program sends 100% of your donation to four standout plant-based feeding projects that nourish people, generate income for long-term sustainability, conserve scarce natural resources, and protect the environment.

We work with country-specific, grassroots organizations and local residents who are already implementing culturally appropriate plant-based feeding programs in their communities, and who are in need of funding and partnership support.

It’s relevant to note that many cultures and traditions are traditionally heavily plant-based, with animal foods consumed sparingly, and largely considered a luxury. Supporting locally-run programs that strengthen plant-based feeding and farming projects in these regions is not just better for animals, it’s better for the environment and ecosystems—and thus the people— of these communities as well.