Like me, you might be accustomed to seeing percentage figures on posters and elsewhere, indicating livestock’s share of greenhouse gas emissions. Here’s an image showing a poster from the People’s Climate March in New York in September, 2014.

Like me, you might be accustomed to seeing percentage figures on posters and elsewhere, indicating livestock’s share of greenhouse gas emissions. Here’s an image showing a poster from the People’s Climate March in New York in September, 2014.

I’m not keen on quoting figures indicating livestock’s climate change impacts, unless I can try to explain them. Posters are not a great way to do that.

One problem is that, while environmental processes are dynamic, the figures are often portrayed as if they’re set in stone.

Another problem is that the figures depend on whichever factors have been taken into account, which can vary significantly from one report to another.

I commented on that issue in my February, 2013 article “Omissions of Emissions: A Critical Climate Change Issue“. [1] I stated that critical under-reporting of livestock’s impact occurs in many “official” figures because relevant factors are omitted entirely, classified under non-livestock headings, or considered but with conservative calculations.

An example of the latter is methane’s impact based on a 100-year, rather than 20-year, “global warming potential” (GWP). Methane is many times more potent than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas, and more so over a 20 year time horizon than 100 years. More on that below.

So while figures are often portrayed as being absolute, they should ideally be qualified so as to explain how they have been arrived at. That might not be very practical, but the issues are complex and cannot always be conveyed appropriately with just a few words or numbers.

Some prominent claims

Livestock reported to be responsible for 18 percent of emissions (which is more than transport)

In its 2006 “Livestock’s Long Shadow” report, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) stated that livestock’s emissions represented 18 percent of the global total in the 2005 reference period. The figure was said to be higher than transport’s share. [2]

In September 2013, the FAO reduced its estimate of livestock’s share to14.5 percent, yet that figure seems to have received relatively little attention. [3] As with “Livestock’s Long Shadow”, the reference period was 2005, but the assessment methodology had been amended. [4] The reasoning was that the FAO had used or relied on different methods for assessing the relative emissions of livestock and transport. In other words, they had not compared “apples with apples”. [5]

Despite the amended approach, both the 2006 and 2013 reports included emissions from fertiliser and feed production, land clearing, manure management, enteric fermentation (producing methane in the animal’s digestive system) and transportation of livestock animals and their feed. Both were based on the conservative 100-year GWP for methane.

Livestock reported to be responsible for at least 51 percent of emissions

The suggestion that livestock are responsible for at least 51 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions came from a 2009 World Watch magazine article by Robert Goodland and Jeff Anhang. [6] Goodland was the lead environmental adviser to the World Bank, and Anhang is a research officer and environmental specialist at the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation.

The article was effectively a critique of “Livestock’s Long Shadow”, with amended figures reflecting the authors’ concerns over the report. The authors took into account various factors, including: livestock respiration; 20-year GWP for livestock-related methane; and some allowance for foregone carbon sequestration on land previously cleared.

1. Livestock respiration

The authors argued that livestock respiration was overwhelming photosynthesis in absorbing carbon due to the massive human-driven increase in livestock numbers and removal of vegetation. Goodland subsequently stated, “In our assessment, reality no longer reflects the old model of the carbon cycle, in which photosynthesis balanced respiration”. [7]

Some have argued against the inclusion of respiration. Based on my calculations, by excluding that factor, the analysis would have indicated that livestock’s emissions represented 43 percent of the global total.

2. Methane

Goodland and Anhang applied a 20-year GWP to livestock-related methane emissions, which is particularly relevant to: (a) potential near-term climate change tipping points; and (b) identification of relatively rapid mitigation measures.

Methane breaks down in the atmosphere relatively quickly, with little remaining after 20 years. As a result, a 100-year GWP greatly understates its shorter-term impact.

Even methane’s near-term impacts can become long-term and irreversible to the extent that they contribute to us reaching tipping points and runaway climate change.

Comments from the IPCC, cited by respected climate change commentator, Joseph Romm, reflect the validity of using a 20-year GWP:

“There is no scientific argument for selecting 100 years compared with other choices (Fuglestvedt et al., 2003; Shine, 2009). The choice of time horizon is a value judgement since it depends on the relative weight assigned to effects at different times.” [8]

A possible cause for concern in this case is that the authors did not adopt the same approach for non-livestock methane emissions. Goodland has since stated, “Because we questioned many aspects of the FAO’s work, we were reluctant to use their figures for methane, but did so anyway for livestock methane because we couldn’t find a more reliable figure”. [9]

Goodland has argued that the impact of such an approach would have been more than offset by the fact that the number of livestock animals they based their assessments on (being the number used in “Livestock’s Long Shadow”) was far below the figure of 56 billion that the FAO’s statistical division had reported in 2007. He and Anhang became aware of the higher figure after their article was published.

The authors used the IPCC’s GWP estimate of 72 that applied at the time of the article. The IPCC has since increased the figure to 86 (incorporating carbon cycle feedbacks), while NASA estimates a figure of 105. [10]

With the rapid increase in extraction of unconventional fossil fuels since 2005, the growth in other anthropogenic sources of methane may have caused livestock’s share of emissions to reduce from what it would otherwise have been.

3. Foregone sequestration

The FAO allowed for emissions from land clearing in the year such changes occurred, with loss of carbon from vegetation and soil. However, it did not allow for the resultant ongoing loss of carbon sequestration.

Goodland and Anhang sought to allow for that factor to some extent. They suggested the possibility of allowing land that has been cleared for livestock grazing or feed crop production to regenerate as forest, thereby mitigating “as much as half (or even more) of anthropogenic GHGs” [greenhouse gases]. They argued that the land could, alternatively, be used to grow crops for direct human consumption or crops that could be converted to biofuels, thereby reducing our reliance on coal. They used the biofuel scenario in their calculations, incorporating the greenhouse gas emissions from the coal that is continuing to be used in lieu of the biofuels.

Goodland’s response to feedback to the 2009 World Watch article can be seen in his March/April, 2010 article, “‘Livestock and Climate Change’: Critical Comments and Responses“ (referred to above).

Australian Emissions (Note: the author lives in Australia)

Estimates of animal agriculture’s share of Australian emissions range from the official figure of around 10 percent to 49 percent.

The Australian government’s 2012 National Inventory Report used a figure of 10.9 percent, representing the aggregate of: (a) enteric fermentation in the digestive systems of ruminant animals; and (b) manure management. The figure was based on a 100-year GWP for methane. [11]

The 49 percent figure is from the land use plan released in October 2014 by Beyond Zero Emissions and Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute (The University of Melbourne). The figure allows for factors such as: a 20-year GWP; livestock related land clearing and subsequent soil carbon loss; and livestock related non-carbon dioxide warming agents such as carbon monoxide and tropospheric ozone. [12]

The overall figure for animal agriculture may actually be higher than 49 percent using BZE’s calculations, as they have reported it solely in relation to rangeland grazing. However, their figure for all agriculture is only marginally higher, at 54 percent.

The main message

Regardless of which approach is adopted, the key message must be that we will not overcome climate change without urgent action on both fossil fuels and animal agriculture.

The precise percentage share of the many contributors to greenhouse gas emissions matters little in that context.

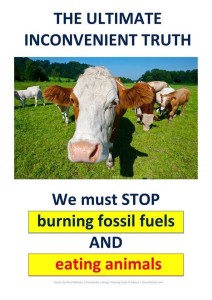

Here’s my contribution to the world of posters, which I like to believe accurately represents our current position.

Additional Comments

A large proportion of the organisations that partnered with the FAO in reviewing its methodology were major participants in the livestock sector. They included the European Feed Manufacturers’ Federation, the International Dairy Federation, the International Meat Secretariat, the International Egg Commission, and the International Poultry Council. [13]

The FAO is now indicating that meat consumption will increase by more than 70 percent by 2050, and has suggested various approaches for reducing relevant emissions. However, any improvement in the emissions intensity of production would be marginal relative to the reductions that could be achieved by a general move toward plant-based products.

The partnership also included the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), which has been accused of working with major business organisations that allegedly use the WWF brand to help improve their green credentials, while acting against the interests of the environment. [14]

As I have reported elsewhere, the partnership was chaired by Dr. Frank Mitloehner of the University of California, Davis, who has disclosed research funding from the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association. [15]

References:

[1] Mahony, P., “Omissions of Emissions: A Critical Climate Change Issue“, Terrastendo, 9th February, 2013,http://terrastendo.net/2013/02/09/omissions-of-emissions-a-critical-climate-change-issue/ [2] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2006“Livestock’s Long Shadow – Environmental Issues and Concerns”, p. xxi, Rome, http://www.fao.org/docrep/010/a0701e/a0701e00.HTM (Related FAO articles at http://www.fao.org/ag/magazine/0612sp1.htm; andhttp://www.fao.org/newsroom/en/news/2006/1000448/) [3] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 26th September, 2013, “Major cuts of greenhouse gas emissions from livestock within reach”,http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/197608/icode/ [4] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations,“Methodology: Tackling climate change through livestock”,http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/197644/icode/ [5] Brainard, C., “Meat vs Miles”, The Observatory, 29th March, 2010, http://www.cjr.org/the_observatory/meat_vs_miles.php?page=all [6] Goodland, R & Anhang, J, “Livestock and Climate Change – What if the key actors in climate change are cows, pigs, and chickens?”, World Watch, Nov/Dec, 2009, pp 10-19, http://www.worldwatch.org/files /pdf/Livestock%20and%20Climate%20Change.pdf [7] Goodland, R., “Lifting livestock’s long shadow”, Nature Climate Change 3, 2 (2013) doi:10.1038/nclimate1755, Published online 21 December 2012,http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v3/n1/full/nclimate1755.html and http://www.readcube.com/articles/10.1038/nclimate1755 [8] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Fifth Assessment Report, 2014, http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/, cited in Romm, J., “More Bad News For Fracking: IPCC Warns Methane Traps More Heat”, The Energy Collective, 7th October, 2013,http://theenergycollective.com/josephromm/284336/more-bad-news-fracking-ipcc-warns-methane-traps-much-more-heat-we-thought [9] Goodland, R., “‘Livestock and Climate Change’: Critical Comments and Responses”, World Watch, Mar/Apr, 2010. [10] Schindell, D.T.; Faluvegi, G.; Koch, D.M.; Schmidt, G.A.; Unger, N.; Bauer, S.E. “Improved Attribution of Climate Forcing to Emissions”,Science, 30 October 2009; Vol. 326 no. 5953 pp. 716-718; DOI: 10.1126/science.1174760,http://www.sciencemag.org/content/326/5953/716.figures-only [11] Australian National Greenhouse Accounts National Inventory Report 2012, Volume 1, pp. 39 and 257,http://www.environment.gov.au/climate-change/greenhouse-gas-measurement/publications/national-inventory-report-2012 [12] Beyond Zero Emissions and Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, The University of Melbourne, “Zero Carbon Australia, Land Use: Agriculture and Forestry Discussion Paper”, p. 68 & 97, October, 2014,http://bze.org.au/landuse [13] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “New effort to harmonize measurement of livestock’s environmental impacts”, 4th July, 2012, http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/150555/icode/ [14] Huismann, W., “Panda Leaks: the dark side of the WWF“, cited in Vidal, J., “WWF International accused of ‘selling its soul’ to corporations”,The Guardian, 4th October, 2014,http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/oct/04/wwf-international-selling-its-soul-corporations [15] Goodland, R., “FAO’s New Parternship with the Livestock Industry“,Chomping Climate Change, 20th July, 2012,http://www.chompingclimatechange.org/blog/faos-new-parternship-with-the-livestock-industry