Have you ever heard the claim that 86% of animal feed is inedible to humans? This statistic is often used to imply that animal farming merely uses the waste from farming human food. However, the research behind this figure shows the opposite: animal feed competes with food security. Let’s break it down:

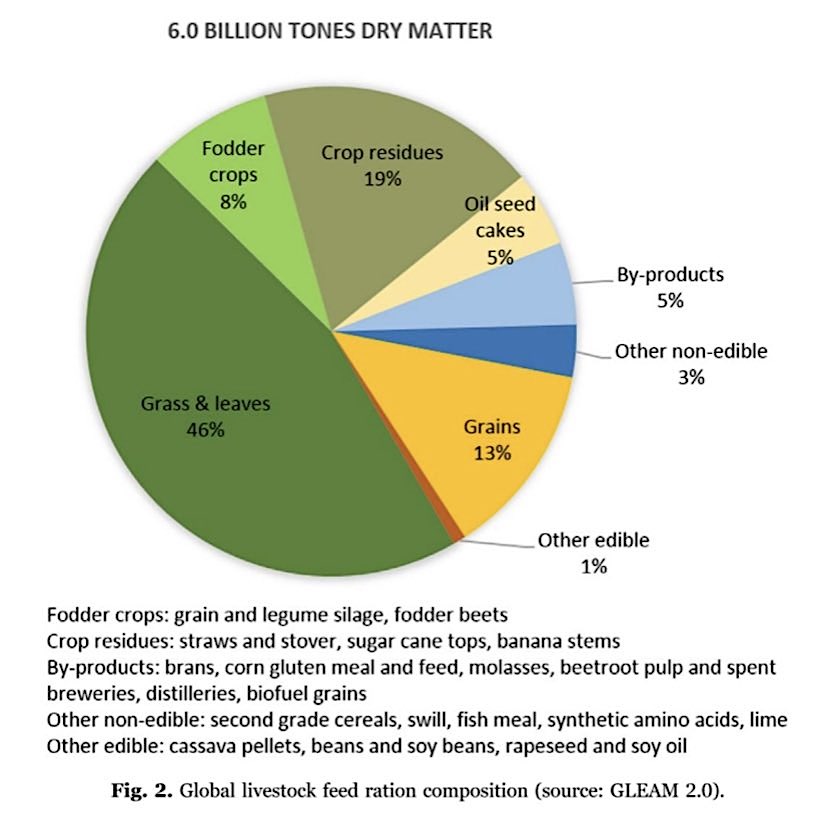

Byproducts and crop residues comprise less than 1/4 of animal feed used globally. The vast majority is either taken from pasture or grown explicitly for animal feed. Growing crops for farmed animals consumes more than 1/3 of global crop production, yet only 12 percent of those calories then become human food.

Byproducts and crop residues comprise less than 1/4 of animal feed used globally. The vast majority is either taken from pasture or grown explicitly for animal feed. Growing crops for farmed animals consumes more than 1/3 of global crop production, yet only 12 percent of those calories then become human food.

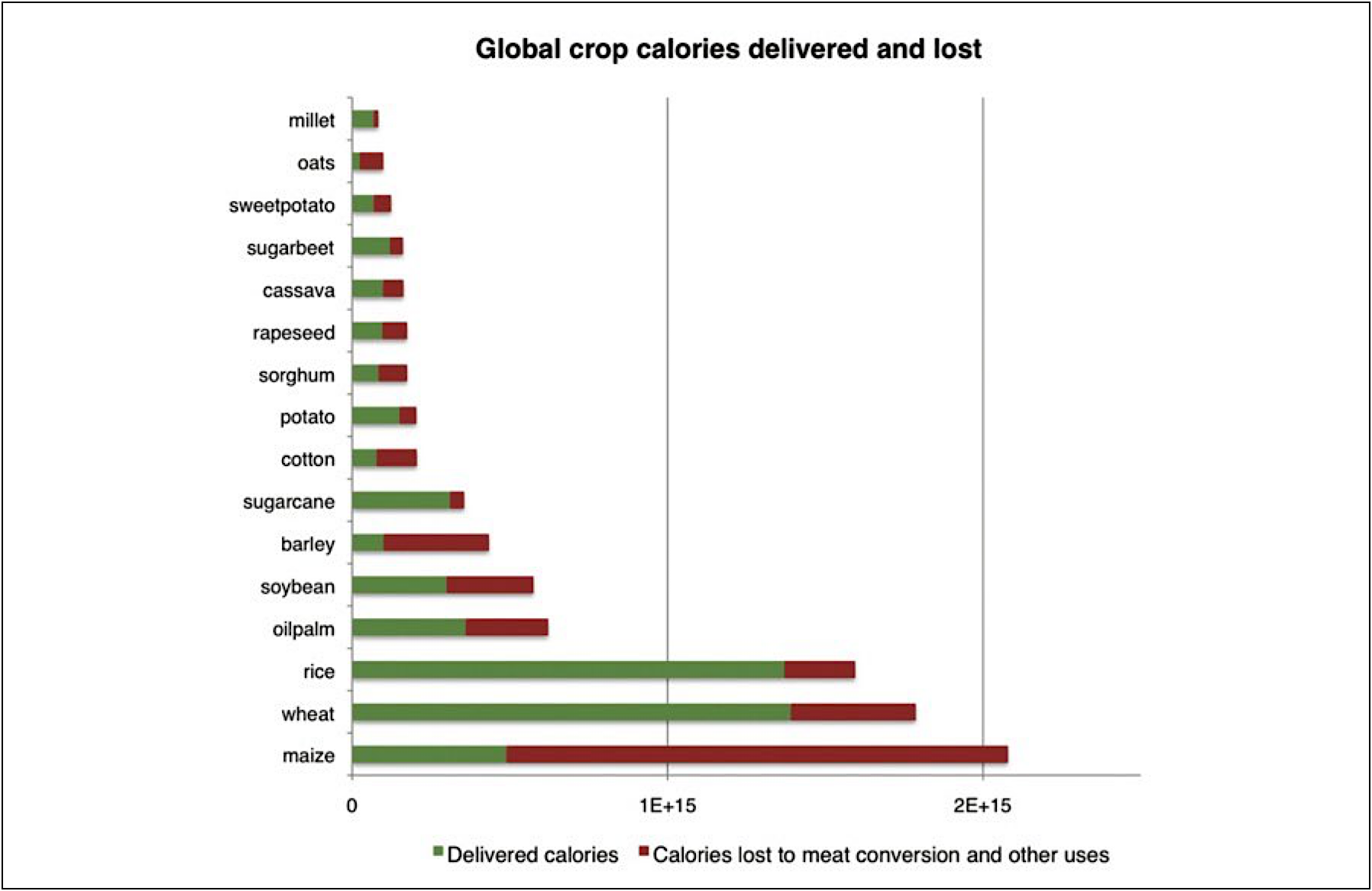

The oft-heard assertion that “We grow enough food to feed 10 billion people,” while true, is typically made without sufficient context. What happens to all that food? Well, we feed vast quantities of it to farmed animals. Some 36% of global crop calories are used for animal feed, of which only 12% becomes human food, due to the metabolic waste inherent in using animals to inefficiently convert "feed" to "food."

Grain used for animal feed by the U.S. alone could feed close to a billion people. Animal agriculture drives hunger by reducing the global food supply. If we want to fight hunger, we need to redirect yields and land used for animal feed to human consumption.

Furthermore, almost half of all animal feed comes from “grass and leaves.” This refers to so-called pasture-feeding, which sounds benign and "natural." But hidden in that innocuous moniker are all the artificially bred cows, sheep, and goats feeding on ecosystems like U.S. public lands and slashed-and-burned rainforests.

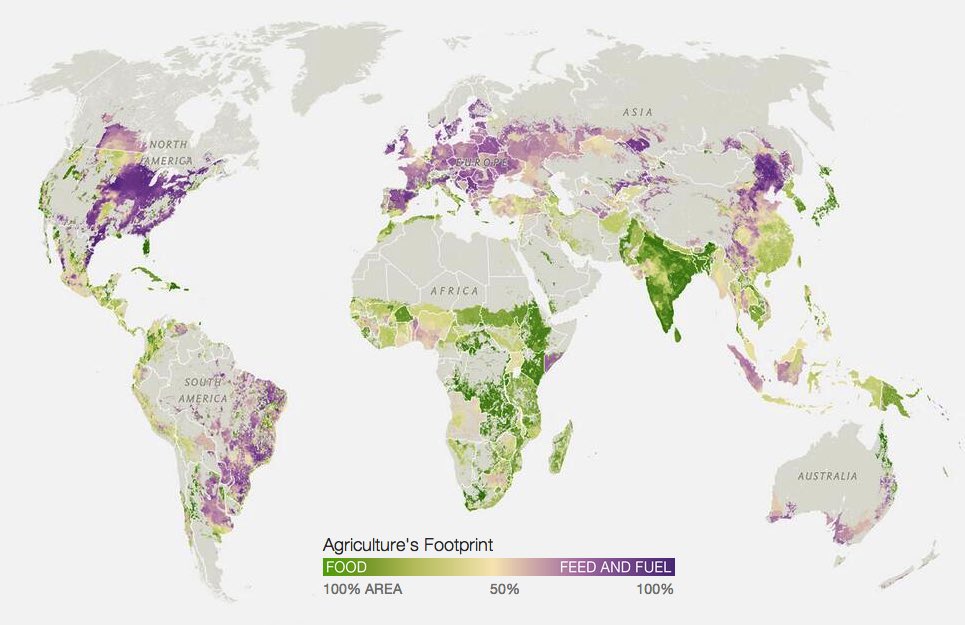

Grass-feeding is framed as the sustainable, ecological alternative to "factory farm" feedlots, yet it drives more than half of tropical deforestation. If we wanted to meet global meat and dairy demand by feeding everyone pasture-fed animals, we would need vastly more land than exists on this planet.

“Inedible to humans” is not a synonym for food waste. The process of converting “feed” to “food” through animal agriculture involves far more food loss— otherwise known as opportunity cost— than all the food waste that occurs in our entire agricultural system— including both production and consumption.

In reality, the myth that feed production for animal agriculture does not compete with human food security is part of a coordinated misinformation campaign by the meat industry. The truth is that the inequitable distribution of food required for farming animal products is a primary driver of global food insecurity.

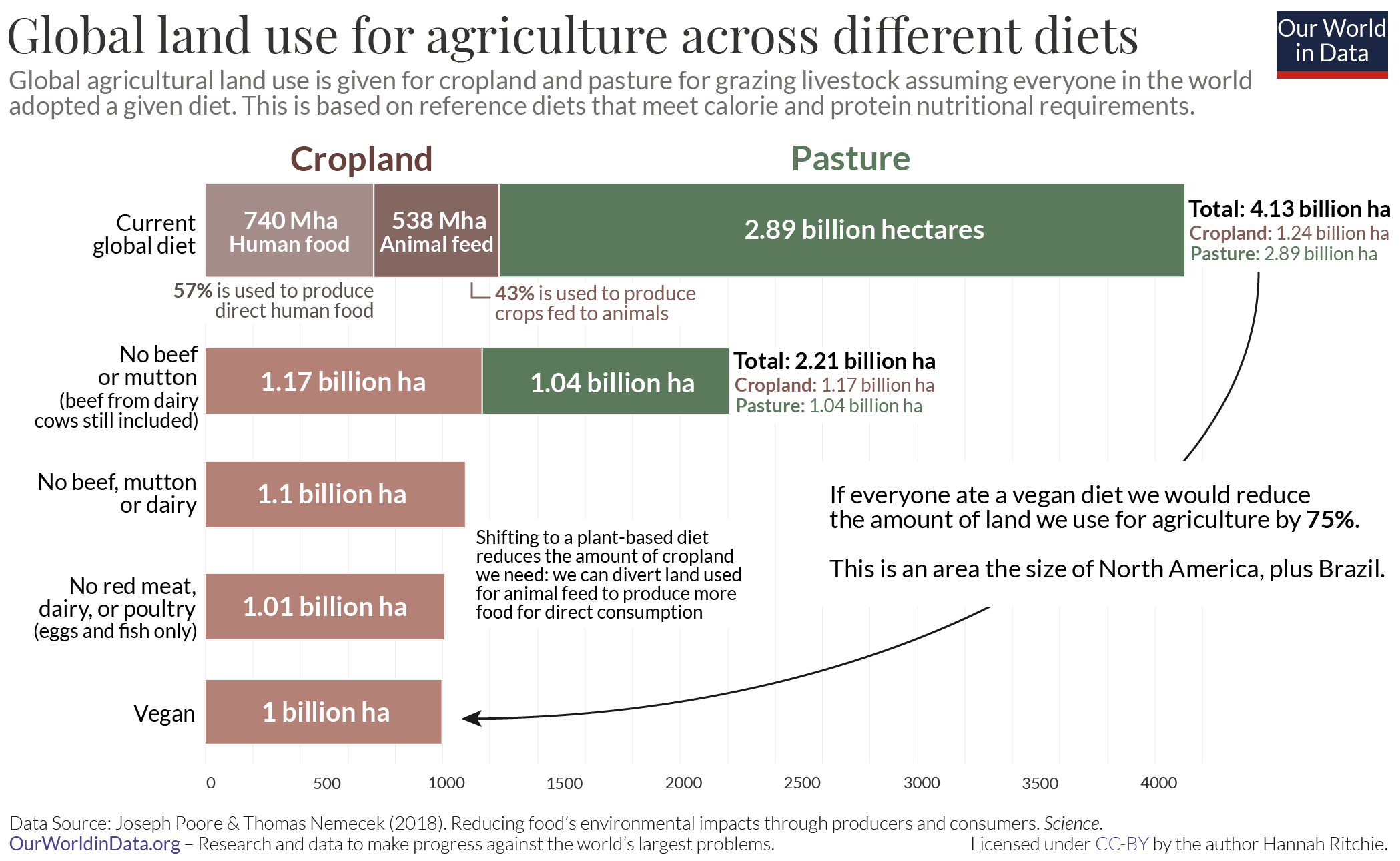

It’s not simply an issue of distribution. Hoarding and waste are factors, but small in comparison to the appropriation of crops for animal farming. If we grew plant foods directly for human consumption, we would need less than a quarter of the agricultural land we use today and would cut food's climate emissions and water pollution in half.

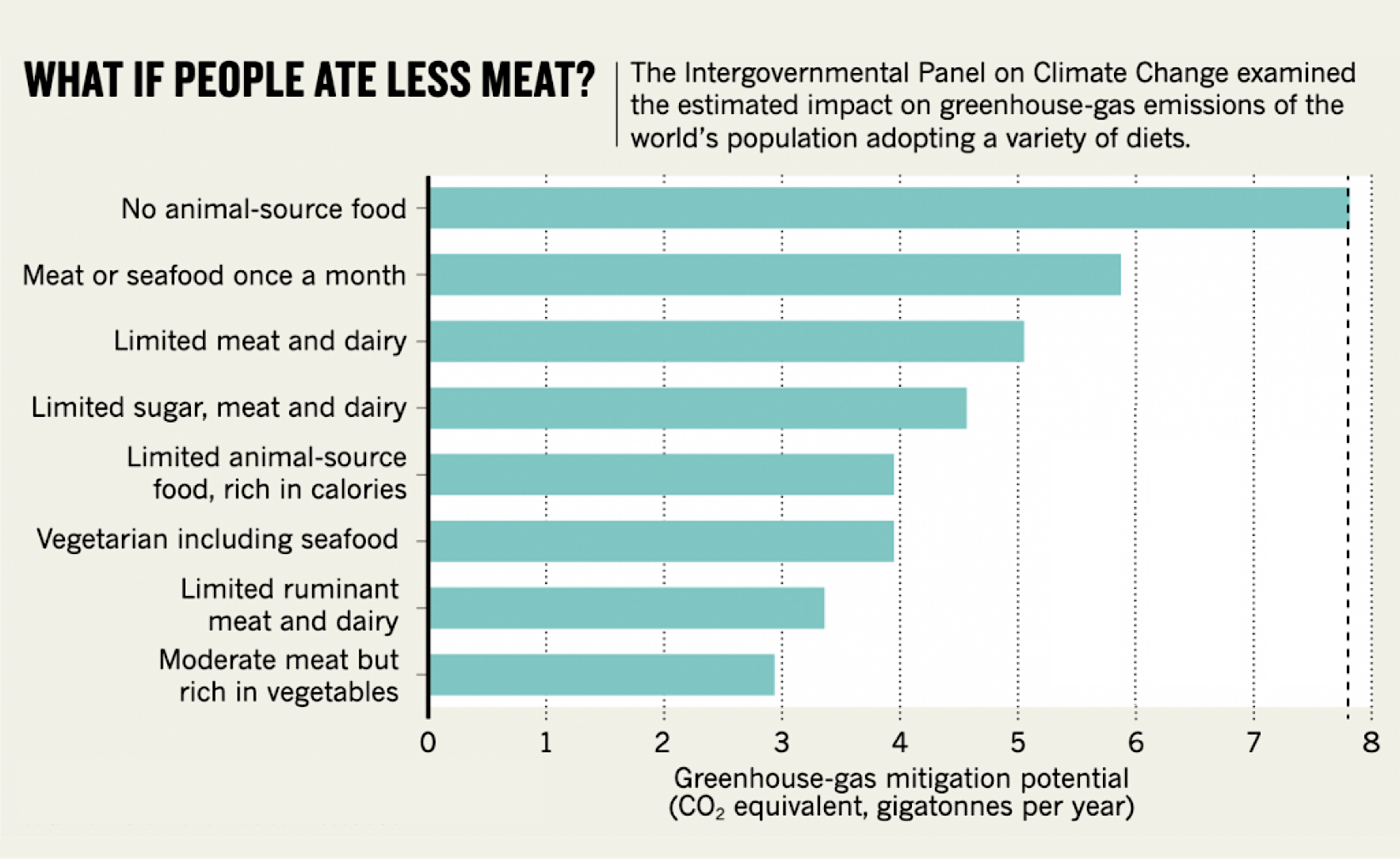

"Today, and probably into the future, dietary change can deliver environmental benefits on a scale not achievable by producers. Moving from current diets to a diet that excludes animal products has transformative potential, reducing food’s land use by 3.1 (2.8 to 3.3) billion ha (a 76% reduction), including a 19% reduction in arable land; food’s GHG emissions by 6.6 (5.5 to 7.4) billion metric tons of CO2eq (a 49% reduction); acidification by 50% (45 to 54%); eutrophication by 49% (37 to 56%); and scarcity-weighted freshwater withdrawals by 19% (−5 to 32%)." —Poore & Nemecek, Reducing Food's Environmental Impacts Through Producers and Consumers

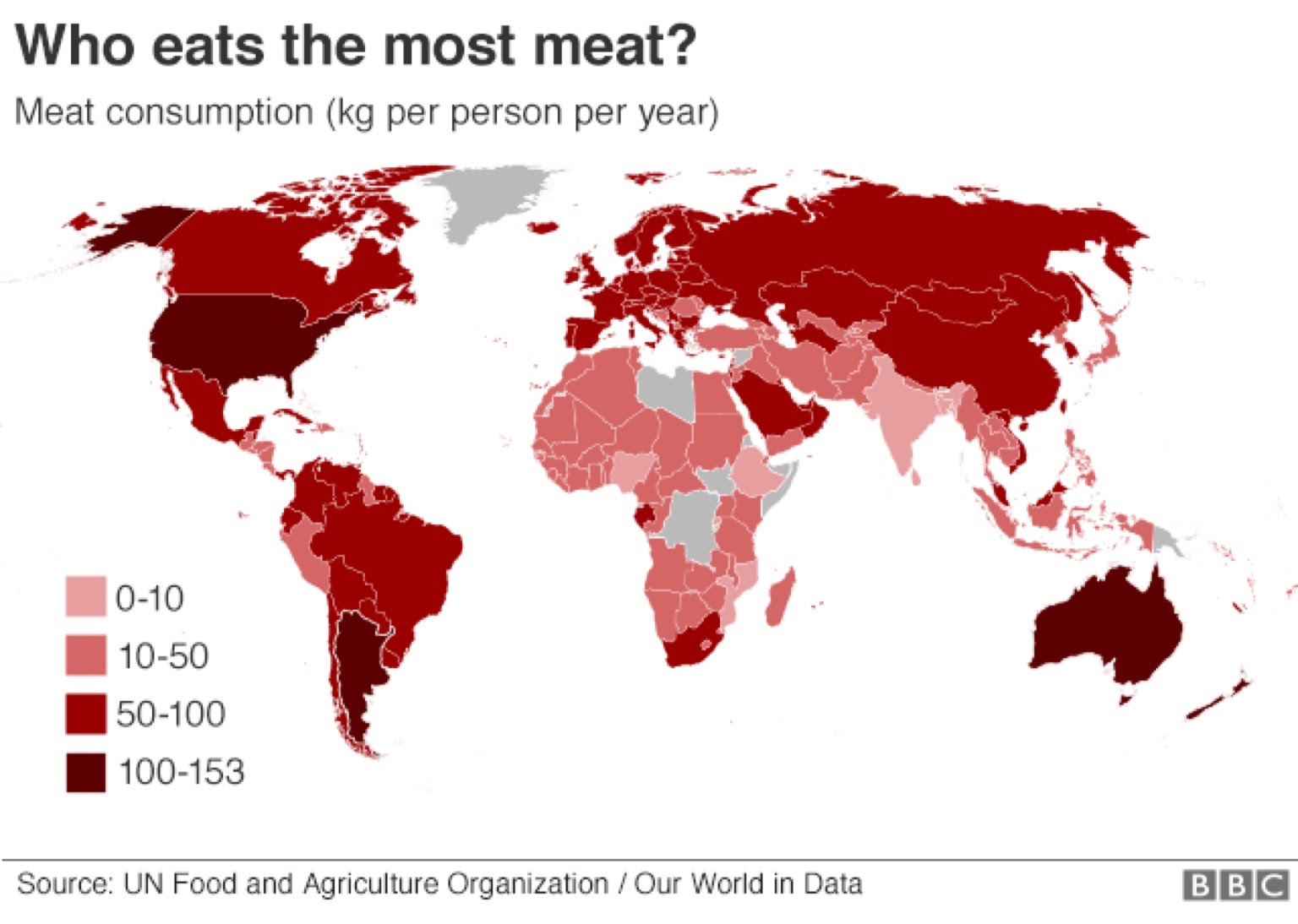

While it’s correct to point to capitalism as a reason our food system doesn’t feed 10 billion, we must understand the mechanism: capitalism prioritizes producing luxury commodities like meat and dairy for higher-income countries over staple commodities like beans, grains and potatoes for lower-income ones.

Hunger is a policy choice. The choice by industrialized nations to build animal-based food systems multiplies both resource inputs and waste outputs by roughly an order of magnitude. Ending hunger requires equitably distributing agricultural yields. The first step in this is to address the injustice of appropriating vast amounts of land, water, and crops for the purpose of farming animals.

Spencer Roberts is a science writer, ecologist, engineer, and musician from Colorado. Follow on Twitter @Unpop_Science.